How Christie Wrote

Plots come to me at such odd moments, when I am walking along the street, or examining a hat shop...suddenly a splendid idea comes into my head.

Spending most of her time with imaginary friends, Agatha Clarissa Miller’s unconventional childhood fostered an extraordinary imagination. Against her mother’s wishes, she taught herself to read and had little or no formal education until the age of fifteen or sixteen when she was sent to a finishing school in Paris.

Agatha Christie always said that she had no ambition to be a writer although she made her debut in print at the age of eleven with a poem printed in a local London newspaper. Finding herself in bed with influenza, her mother suggested she write down the stories she was so fond of telling. And so a lifelong passion began. By her late teens she had had several poems published in The Poetry Review and had written a number of short stories. But it was her sister’s challenge to write a detective story that would later spark what would become her illustrious career.

Agatha Christie wrote about the world she knew and saw, drawing on the military gentlemen, lords and ladies, spinsters, widows and doctors of her family’s circle of friends and acquaintances. She was a natural observer and her descriptions of village politics, local rivalries and family jealousies are often painfully accurate. Mathew Prichard describes her as a “person who listened more than she talked, who saw more than she was seen.”

The most everyday events and casual observations could trigger the idea for a new plot. Her second book The Secret Adversary stemmed from a conversation overheard in a tea shop: “Two people were talking at a table nearby, discussing somebody called Jane Fish… That, I thought, would make a good beginning to a story — a name overheard at a tea shop — an unusual name, so that whoever heard it remembered it. A name like Jane Fish, or perhaps Jane Finn would be even better.”

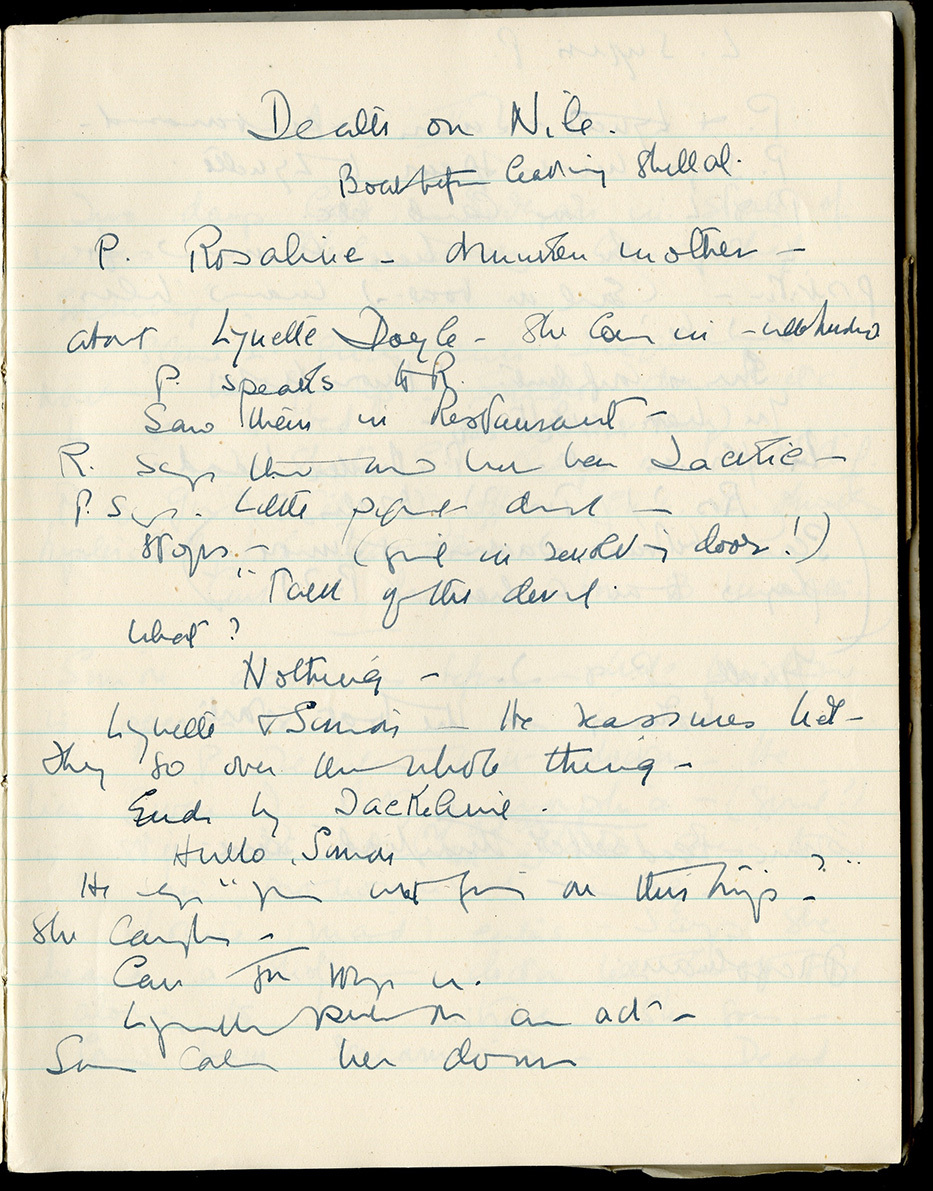

And how were these ideas turned into novels? She made endless notes in dozens of notebooks, jotting down erratic ideas and potential plots and characters as they came to her “I usually have about half a dozen (notebooks) on hand and I used to make notes in them of ideas that struck me, or about some poison or drug, or a clever little bit of swindling that I had read about in the paper”.

Of the more than one hundred notebooks that must have existed, 73 have survived and John Curran’s detailed and thorough analysis provides a veritable treasure trove of revelations about her stories and how they evolved (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks). The notebooks themselves include previously unpublished material and are an intriguing look into her mind and craft. The seeds for several stories are easily identified. In 1963 a notebook held details of a plot in development: “West Indian book – Miss M? Poirot . . . B & E apparently devoted – actually B and G (Georgina) had affair for years . . . old ‘frog’ Major knows – has seen him before – he is killed”

A Caribbean Mystery was published in 1964 with the “Old Frog” as the novel’s first victim. The Caribbean island is beautifully described and was probably based on St. Lucia, an island that Christie had visited on holiday. But many of the hundreds of plots and red herrings from her fertile imagination never actually made it into print and as she herself said: “Nothing turns out quite in the way that you thought it would when you are sketching out notes for the first chapter, or walking about muttering to yourself and seeing a story unroll.”

She spent the majority of time with each book working out all the plot details and clues in her head or her notebooks before she actually started writing. Her son-in-law Anthony Hicks once said: “You never saw her writing”, she never “shut herself away, like other writers do.”

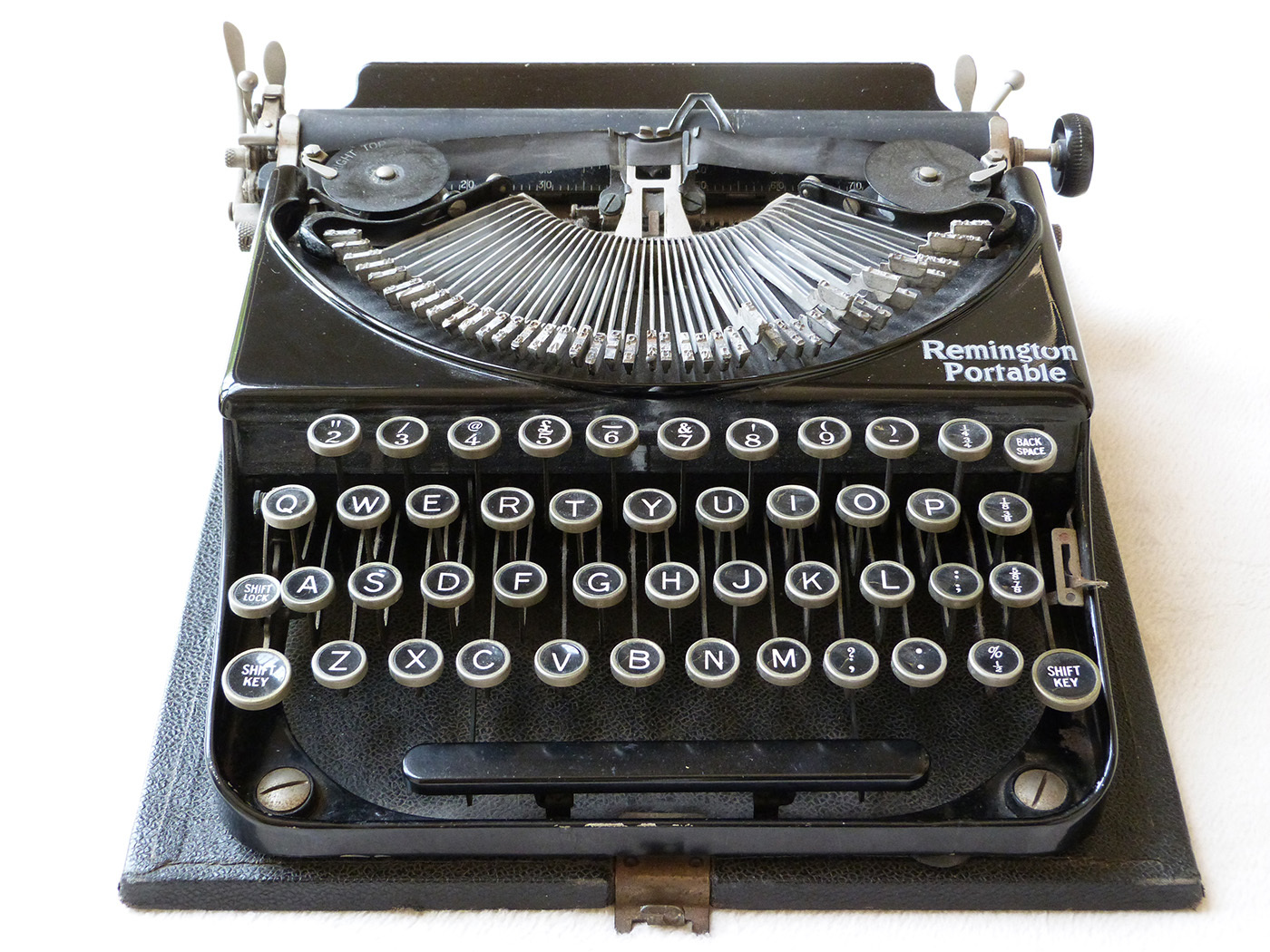

As grandson Mathew Prichard explains, “she then used to dictate her stories into a machine called a Dictaphone and then a secretary typed this up into a typescript, which my grandmother would correct by hand. I think that, before the war, before Dictaphones were invented, she probably used to write the stories out in longhand and then somebody used to type them. She wasn’t very mechanical, she wrote in a very natural way and she wrote very quickly. I think a book used to take her, in the 1950s, just a couple of months to write and then a month to revise before it was sent off to the publishers. Once the whole process of writing the book had finished then sometimes she used to read the stories to us after dinner, one chapter or two chapters at a time. I think we were used as her guinea pigs at that stage; to find out what the reaction of the general public would be. Of course, apart from my family, there were usually some other guests here and reactions were very different. Only my mother always knew who the murderer was, the rest of us were sometimes successful and sometimes not. My grandfather was usually asleep for most of the time that these stories were read but the rest of us were usually very attentive. It was a lovely family occasion and then a couple of months later we would see these stories in the bookshops.”

USA

USA